A Navigators perspective

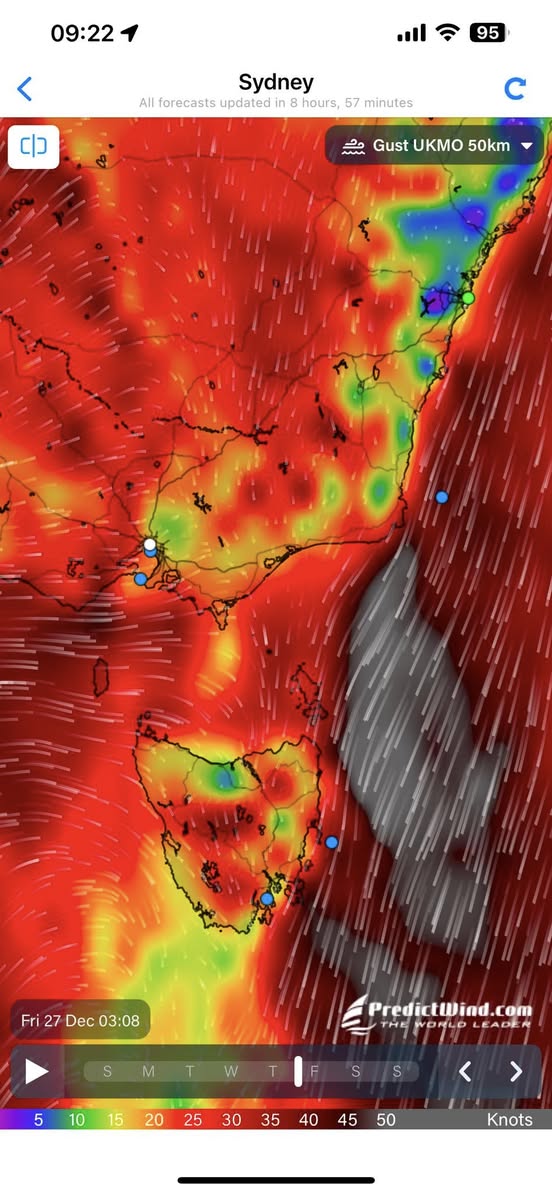

Sydney Hobart Yacht Race 2024 completed and what a year! The first 24 hours were particularly intense, hammering downwind under +40kt winds in turbulent seas. The boat needed a lot of guidance and on our watch Cahal, Tommy and myself did 20 minute rotations at the helm in an attempt to keep our arms and minds at peak performance in taxing conditions. As we worked south and the sun set, the wind rotated forcing us into a beat (sailing right into the wind). Pounding into the waves the conditions began to take their toll. By the end of the morning there had been two deaths, a man overboard, and many injuries, shredded sails, and damaged boats. Nearly a third of the fleet had retired including big respected boats with professional crews such as Comanche.

As we soldiered on, rogue waves aggressively slammed into our side continually threatening to throw our boat over. Our own crew below thrown around like rag dolls. Doors slammed on hands and faces, locked drawers burst from their brackets and shot across the room, shoulders were dislocated, and crew were repeatedly catapulted dangerously from one side of the boat to the other. With another 12 hours of these conditions forecasted, the toll seemed unbearable and increasingly unsafe.

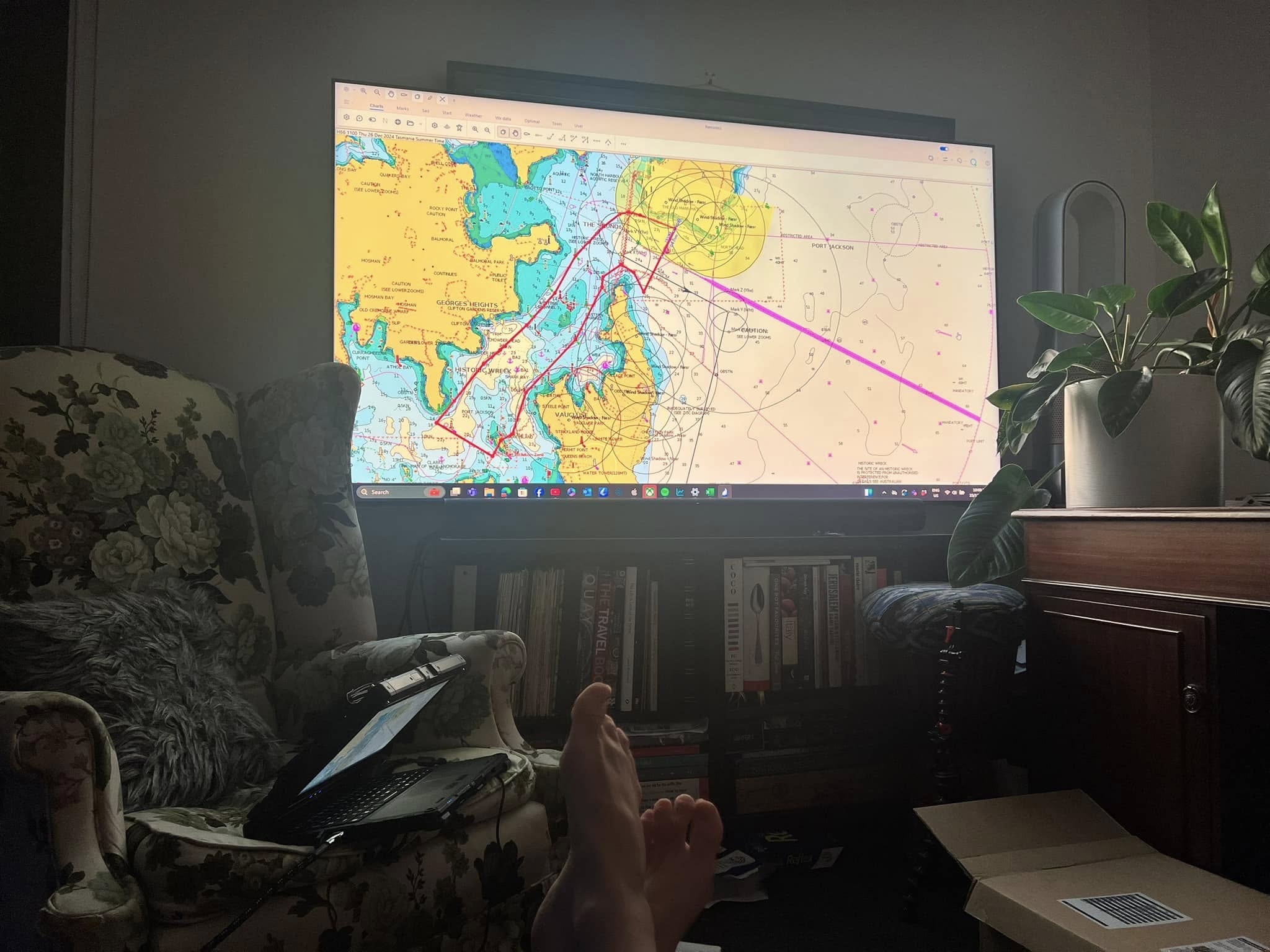

With concerns onboard raising, we changed course and started making a beeline for Eden, a renown safe harbour. As we got closer inshore the sea state began to settle and from a Navigation perspective I began to work through our options and their implications. Presenting this, serious discussions were had with all crew, and anchoring overnight to wait for the current system to pass through was a growing consensus. Yet this delay would likely mean getting caught without wind the following day leaving us to wait for another system to ride south.

In the end, we decided to press on. Inefficiently meandering around Eden we took a moment to clean the boat up, do some safety checks, regroup mentally, and then pressed on under a modified risk-mitigated route. Staying closer inshore, we worked our way down the coast in less violent waters before reaching the notoriously dangerous Bass Strait. With local observations in the Strait showing 43kts and gusting to 60kts, we were nervous about what might be faced after losing the protection of land.

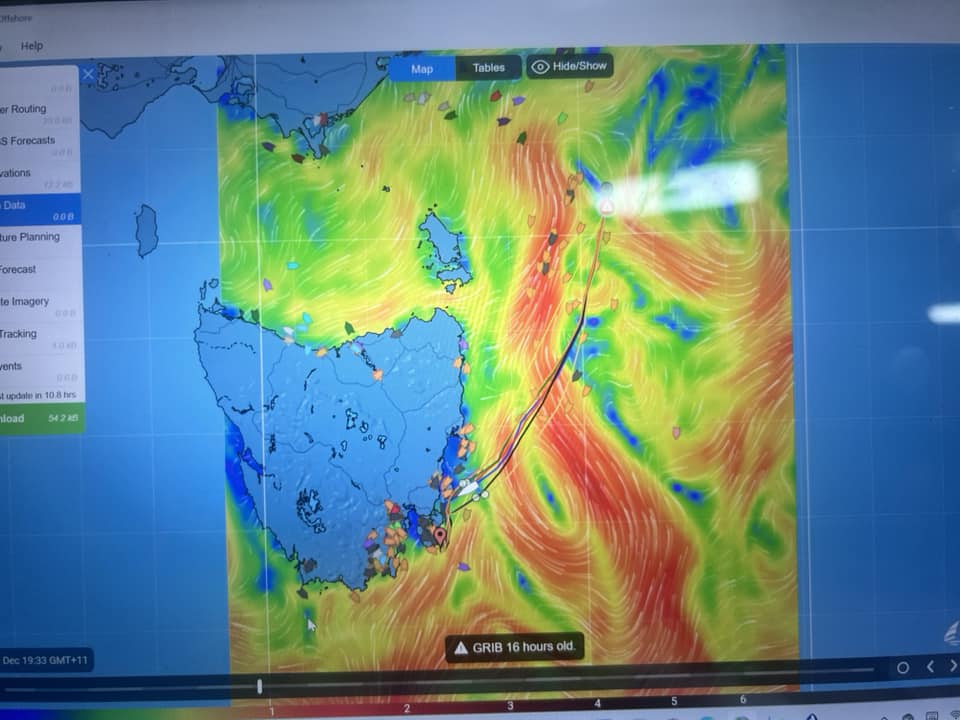

By the time we cleared the final southern-most tip of Victoria, the ominous crossing turned out to be a dream. The wind reduced to a much calmer 25-35kts, and with surprisingly flat seas and a great reaching angle, we flew across Bass Strait in what was one of my easiest crossings to date. The key problem at this stage was 2.8kts of un-forecasted current against us, instead of the predicted 2kts of current we would have with us! Frustratingly, this went on for a full day absolutely destroying our SOG (Speed Over Ground)! I felt pretty trapped at this stage, unsure of how to escape. We needed to work West but there was an even worse band of current theoretically walling us off from this! Heading West would also make us vulnerable to the weaker lee shore winds of Tasmania. Or perhaps we’d miss the good current and we should head further East to find it? But if we did this, and it wasn’t there, then we’d have wasted a lot of time and be even further from our destination! To complicate the matter further, there was meant to be a good current further south that would send us directly across to our next mark. But was this worth waiting for whilst our SOG continued to suffer?

As I ran the numbers and weighed up the implications of each, boats who hadn’t gone out as far East began to creep ahead. It was demoralising. Pulling two double shifts, rapidly researching and spring-boarding ideas with Petie my co-navigator, and after discussions with Greg the skipper, we decided the risk/reward equation was stronger to avoid the westerly wall of current and instead continuing heading south in the hope of eventually riding good current back in. In hindsight it wasn’t ideal to be where we were. But this seemed the best strategy based on where we’d ended up.

Thankfully, it turned out better to continue on south rather than heading west early. Boats behind us that began to cross the western wall of current early quickly fell behind. And whilst boats who had headed West in to Tasmania much earlier had seemed to have clearly made the best decision. They were beginning to slow as the lack of lee shore breeze validated what I had been trying to keep us from. Reaching in to the south-easternmost tip of Tasmania, we began to accelerate past westerly boats and catch up to our competition ahead!

Sadly, I didn’t have much time to enjoy this small victory. It was clear the breeze would soon drop out entirely and a strategy was needed to both navigate through, and capitalise on this potential opportunity. There seemed one key spot where the wind would build in from first. Yet heading to this would mean veering off the layline and taking a less efficient route in the hope of picking up something that might not even be there. To further raise the stakes, the strategy would only work if we could get there before the wind died out - and I wasn’t sure we could.

Shifting course for this new target location, we tried to push the boat harder, and my attention went to dodging, or threading the needle through the thinnest parts, of a number of small low pressure systems rolling out from Tasmania that would have slowed us down if we got caught in them. We seemed to manage this perfectly and ended the day within 2nm of the target location before we were becalmed. Drifting without steerage I wondered if the risk would pay off.

Thankfully, it wasn’t long before the wind began to build from the predicted location and we began to accelerate again! This part of the race was a little messy reminding me how tricky light wind sailing can be on crews. Tempted by boat speed and steerage over VMG (Velocity Made Good - how fast you’re moving ‘as the crow flies’ to your mark) we headed too far West. Then put up the A1 spinnaker which I mistakenly expected to be a deep running kite, but it wasn’t, and pulled us further west and continued to undermine our VMG. Waiting a little too long, we quickly swapped the “A1” out for an A2 which thankfully turned out to be great. Whilst it took some time to make back the gains we’d lost, and more easterly boats accelerated off before us in the new breeze, it wasn’t a major issue. We could run faster and deeper with the A2 up, and soon began to chase them back down.

As the wind built back up to 20kts, we turned around Tasman Island just as the sun rose and spectacularly illuminated the stunning dolerite cliff! As the sun continued to rise so did our spirits. It had been a tough race physically and emotionally but the end was now in sight! Music played from the cockpit and fingers on the rail tapped along to the beat as we reached toward the mouth of the Derwent. Recognising the powerful difference good jib trim can make in those type of reaching conditions, I left Petie to the remaining navigation and focused almost solely on maximising speed. With Mati skillfully trimming the main and Cahal masterfully at the wheel, we had our best technical performance of the race at this moment well exceeding our polars for a number of hours.

Whilst the Derwent River has a deservedly devilish reputation. It treated us well! In return, we manage to climb past a few more boats as we tacked north toward the finish line. Much to my co-navigator Petie’s delight, we found good wind along the Western side. Something he had cleverly figured would be likely given the prevailing wind direction and surrounding topography. Lee took the helm for the finish as we arrived to applause.

It turned out to be one of the toughest Sydney to Hobart’s in the races 79 year history. And the memorial service the day after for the two lives lost was a stark reminder of this. Our own crew within VHF range to witness the traumatic unfolding of these tragedies. Only those out there will understand exactly what the 2024 race was like. Yet we stand alongside scores of sailors throughout time who have learned how powerful, violent, and relentless the oceans and winds can be.

When I signed up for this race, I underestimated how much it would mean to me. How special it would feel finishing in Hobart where I’ve unexpectedly spent so much time this year. And how much the race meant to other crew on the boat too. Completing a Sydney to Hobart is no small feat and I now understand that each of my fellow crew had something significant the race meant to them, or that they’ve taken from the experience.

I also underestimated the unique bond we would form, and the love, respect, and enjoyment I would find for each of them. Between watches I would often lie in bed, violently jolted by the slamming waves, but smiling about something I’d enjoyed or admired that last watch about one of my fellow crew. Each of them so talented and with such strong and admirable character. At no point did I ever feel unsafe with any of them.

The race may have finished. But something from it lives on. At times it gave us fear, exhaustion, exhilaration, and connection. But it’s mainly connection that remains. The sea tests you. But it also roots you, deeply and irrevocably, in the people that see you through. And it reminds us that survival, in all its forms, is its own kind of victory. We didn’t just sail the Sydney to Hobart. We became part of it. Of its histories, its tragedies, and its victories. Out there, every decision matters. And consequences for mistakes can be high. But in the end, it’s the small moments of beauty we share - the silent and unified preparedness before the tack, the laughter between shifts, the shared wonder of cliffs and dolphins and sunrises - that will linger long after the salt fades and the sails are stowed.

Thanks for some of the photos: Elsa + Jules

.jpeg)